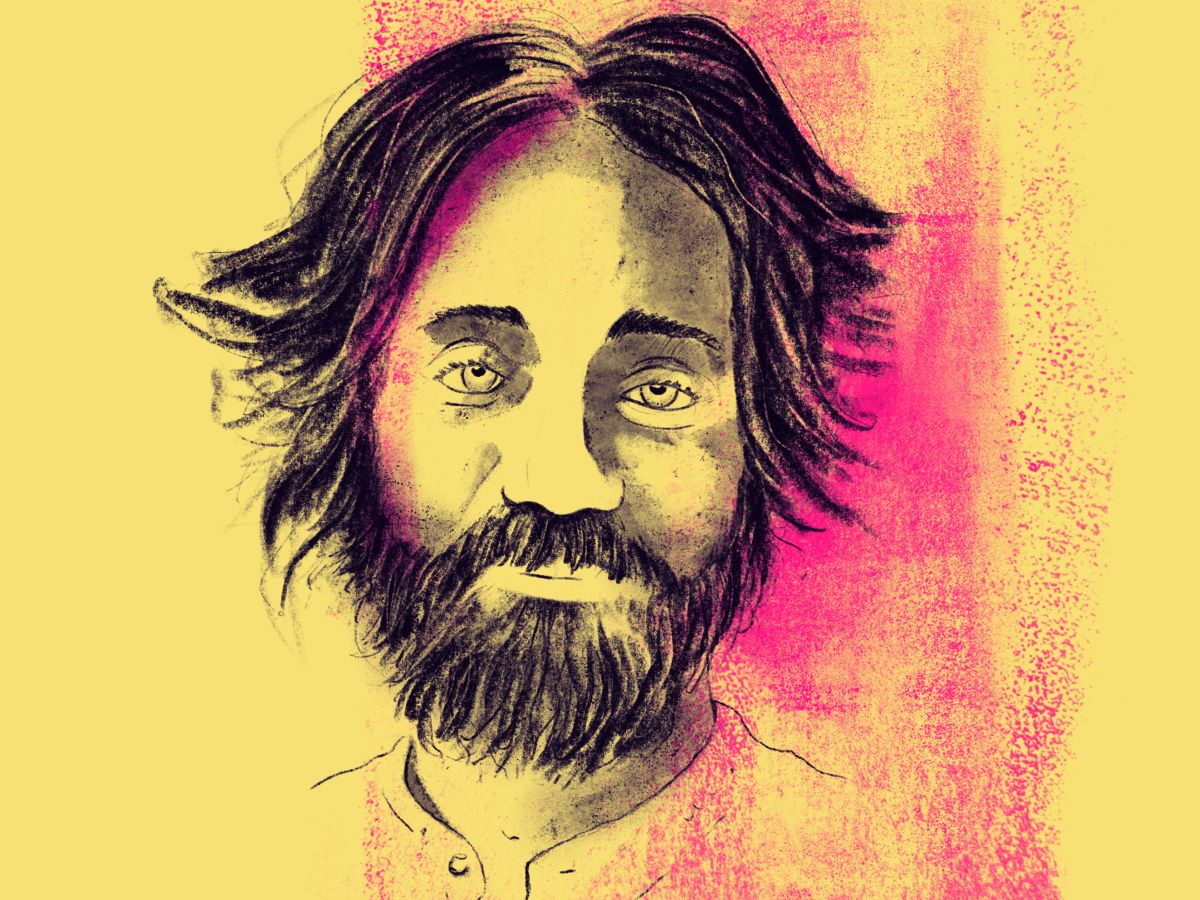

Profile of cartoonist Aseem Trivedi

'In India, the government wants complete control over the stories people see, read and hear'

A drawing can hurt more than an opinion piece. Cartoonists of all countries can attest to that, and the loudest confirmation is the silence of those who were truly silenced. Aseem Trivedi's story illustrates how power reacts when its mistakes and shortcomings are exposed.

India is rightly proud of its democratic credentials and its tradition of independent judiciary and free speech. In early October, however, there was not much of that freedom and pride to be found. The front pages of newspapers and talk among journalists all focused on the morning raid that the court and police had launched against 46 journalists and employees of newssite Newsclick.

That had made it clear that there are apparently strict limits to media freedom, and hence to the rule of law in India. The red line seemed to be criticism of government policies, as the interrogations revolved around coverage of protest movements by farmers and minorities. Those who bewail the government get away with everything. Those who criticise should fear the morning knock on the door. That was the uncomfortable conclusion of an unexpectedly harsh crackdown on press freedom.

On October six, three days after the raid on Newsclick, I had arranged to meet Aseem Trivedi for a cup of morning coffee. An affable thirty-something who weighs his words, and even when he makes sharp analyses of Indian politics or society, he sounds like a concerned friend.

As a cartoonist, however, he knows damn well that the Indian state has long toes, and an arsenal of laws to silence sharp criticism. He learned this back in 2012, when he was arrested after a lawyer lodged a complaint with a Mumbai court. The crime? Cartoons that were found offensive.

Exposing corruption can damage your health

Aseem Trivedi is a prime example of talent finding its way where school paths end. ‘I left school without a diploma,’ he says. ‘I started drawing and experimenting with cartoons, and it worked out surprisingly well.’ Soon he got a foothold in newspapers and websites, and became a name in the world of cartoonists.

He came fully into his own in 2011, at the age of twenty-four. That year, Trivedi got involved in Anna Hazare’s anti-corruption struggle, a movement that made the then coalition government led by the Congress party particularly nervous. On a website he published biting drawings. The pillar of Ashoka with its four lion heads — India’s national symbol — was transformed into a pillar with four wolf heads, also replacing the original slogan ‘truth shall prevail with ‘corruption prevails’.

Another cartoon showed India’s parliament building as a toilet bowl. Yet another showed a woman being held by a politician and a bureaucrat, while a third figure (“corruption”) prepares to rape her. Caption: gang rape of Mother India.

That doesn’t sound very subtle, you say? ‘Cartoons are always exaggerations,’ says Aseem Trivedi. ‘That’s just their strength. And it allows the other side of the debate to feel indignant.’ The latter seemed to work especially well with his cartoons against corruption. In late 2011, his website was taken offline: the provider simply reported it, the Mumbai police had pressed him with a complaint for offensive and defamatory drawings.

But the internet is a house with lots of rooms, and so all the cartoons were immediately uploaded in a new blog, from where the agitation continued. Until not only the drawing, but also the cartoonist was targeted.

On 8 September 2012, Aseem Trivedi was arrested. Several laws were invoked to justify that intervention, including the old colonial law against sedition (section 124A), section 66A of the Information Technology Act and a 1972 law for the prevention of insults. The charge of sedition weighed particularly heavily. In 1922, Mahatma Gandhi was also prosecuted under that section of the Penal Code.

His response: ‘I regard Section 124A as the prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Act designed to suppress the freedom of expression of citizens.’ Dissatisfaction with policies can never be a crime, Gandhi argued, ‘so long as that opinion does not contemplate, encourage or incites violence.’

And he concluded: ‘I know that some of India’s most beloved patriots have been condemned under this law. I therefore consider it a privilege to be indicted under this section as well.

So Trivedi was in good historical company, but that does not mean he willingly settled for the role of martyr. He initially refused to seek bail, refusing to acknowledge the validity of the laws used.

An independent lawyer then filed a demand and Trivedi was allowed to leave prison three days later. Together with the Publishers Guild, he successfully challenged the constitutionality of Section 124A. The IT Act was also repealed in 2015, following the Save Your Voice campaign he helped to organise.

But the complaint about insulting the national symbol and the government remains pending, and could still cost him three years behind bars. It is now scheduled to appear before the court in February 2024. ‘All in all,’ says Aseem Trivedi, ‘the prosecution only encouraged me to involve more in activism.’

Je suis Charlie, Raif, et les autres

There were periods when that activism took the form of cartoons — for example, in his fight against internet laws — and there were other periods when drawing had to give way to organising, protesting and public arguing.

And then there were all those times when putting away an his pencil was not even his own choice, but the decision of organisers or clients who were to afraid to have his name attached to their publication or event. The stigma of the charges outweighed any conviction.

‘It was actually the shock of the attack on Charlie Hebdo as well as the Mumbai government’s reaction to expressions of solidarity that got me drawing again,’ he confesses. He started his own comic book series, in which an artist interacted with the Prophet Mohammed, and an online magazine that provided space to bloggers, artists and journalists from all over the world who were persecuted for their opinions.

The first edition of that magazine featured a series of 50 cartoons Trivedi made in response to the first 50 (of a thousand) lashes Saudi writer and activist Raif Badawi would receive in January 2015. A Cartoon Against Every Lash the series was called, which received worldwide acclaim.

That was the start of his international career. He received commissions from countries like Turkey, Bahrain and Egypt, denouncing authoritarian leaders from East and West. ‘We see the same evolution in so many places,’ sighs Trivedi. ‘Religion is no longer a matter of spirituality, but an identitarian and political issue. Power is not used for the good of citizens, but for the glorification of leaders, and for the value of stock exchange shares of their business friends.’

The shrinking space for free press

In India, argues Aseem Trivedi, press freedom and space for investigative journalism peaked in the first 15 years of this century. ‘Thereafter, public debate was stifled by increasingly authoritarian policies. The public forum was explicitly taken over by a loud and aggressive appeal to the majority’s feeling that minorities were being of pampered. Increasingly, the Hindu majority’s fears of terrorism and minorities are also fuelled — and both are nothing more than a disguise for dislike of Muslims.’

Today, most media outlets are hand puppets of the regime, believes not only Trivedi. In the hectic days following the Newsclick raid, sharp editorials also appeared in mainstream newspapers on the attack the government seemed to be launching on the few independent media that remained.

‘The media went through a brief period of critical independence,’ agrees Baijayanta Chakrabharty who works for the Bengali newspaper Ei Samay in Kolkata. ‘But it has not lasted longer than 20 years. Before the years of the Emergency in the 1970s, the media was still largely behind the government, which still based its legitimacy on independence and the fight against colonial oppression.

In the decades around the turn of the millennium, we had the most vibrant media, but after the rise of the BJP, that was already over. Because the BJP exerts pressure through all sorts of avenues: through networks, through ad revenue, through legal avenues…’ The worst thing, Chakrabharty concludes, is that other parties are trying to emulate the BJP’s approach in the states where they are in power.

Doors closed, lights out, camera!

Aseem Trivedi compares the current state of media and politics in India to popular cinemas. ‘What the current majority BJP party wants is for the whole country to become a cinema, where only stories are shown whose script is written by the party, in which the prime minister plays the lead role and whose production it realises itself. When everyone is seated, the doors close and the lights go out, so that all attention is sucked towards the big screen. For propaganda makers, that is the ultimate dream.’

‘It is not that Prime Minister Modi and his government are doing so much worse on the socio-economic front than governments before,’ notes Trivedi. ‘Inequality and poverty have been ignored for decades, education and healthcare get far too little budget, there has never been enough work. The result is that most Indians hardly expect anything from their government.’

Still, he is sharp for Modi: ‘Under the Hindu nationalist party, the government’s indifference to its citizens decays into an active hate discourse against minorities and opposition. This poisons the social climate and threatens the cohesion of society.’

‘The BJP does what it promises,’ he adds. The sounds like appreciation for consistent politics, but he immediately adds ‘that is typical of extremists’. Moreover, according to Aseem Trivedi, this government is no less corrupt than previous governments. ‘In fact, the problem is that the mafia politician has become part of the regular repertoire of Indian politics. Anyone who signs up as a candidate without a caravan of cars or a bunch of goons is not even taken seriously by the electorate.’

If that sounds like a spoken cartoon — an exaggeration to convey the seriousness of the situation — one should take Deepti Kapoor’s recent novel, Age of Vice. The author, a former journalist, fills 544 pages with concrete and credible descriptions of the excesses of local politics in northern India. ‘You need to be bad to win elections in India,’ Aseem Trivedi concludes cynically.